Lake Tahoe Airport has never been without controversy. Photo/LTN file

Publisher’s note: This is one in a series of stories Lake Tahoe News will be running leading up to the 50th anniversary of South Lake Tahoe on Nov. 30.

“He who has the gold, makes the rules.”

– Michael Hotaling, Airport Master Plan consultant, at the March 16, 2015, public meeting

By Joann Eisenbrandt

“You know, the city purchased the airport from the county in 1983 for $1. Maybe we should sell it back,” an attendee at the March 17, 2015, South Lake Tahoe City Council meeting said while looking over alternative configurations for the Lake Tahoe Airport prepared by the master plan consultants.

That $1 purchase price has been a decades-long mainstay of local conversation, often repeated in print as fact. But it’s not true. The airport was not purchased from the county, but rather it was annexed by the city through the LAFCo (Local Agency Formation Commission) process. LAFCo is an independent commission that coordinates changes in local government boundaries. As the LAFCo resolution confirming the annexation states, “There is no monetary consideration for the transfer herein.”

Perhaps the $1 idea came from a staff report from then City Attorney Dennis Crabb at the May 3, 1983, City Council meeting when the annexation was in its early stages. “Too many unknowns exist at this point,” he noted, “to allow the drafting of precise transfer documents,” but added, it can be assumed, “that the transfer will be accomplished for one dollar or other nominal consideration.”

Perhaps the $1 idea came from a staff report from then City Attorney Dennis Crabb at the May 3, 1983, City Council meeting when the annexation was in its early stages. “Too many unknowns exist at this point,” he noted, “to allow the drafting of precise transfer documents,” but added, it can be assumed, “that the transfer will be accomplished for one dollar or other nominal consideration.”

Del Laine, former city councilwoman and mayor, recalls another $1 sale offer in the late 1970s or early ’80s by former El Dorado County Supervisor Bill Johnson.

“It was tempting,” she told Lake Tahoe News, “because it also came with the promise of a two-year subsidy.” Johnson does not remember that specific offer, and no written confirmation could be found, but he agrees, “There was always some conversation about the cost of running the airport. From my standpoint, it was always a matter of money.”

Of course the devil is in the details. There was no monetary consideration for the 1983 transfer, but the city was responsible for costs “incidental to the fulfillment by the parties hereto of the transfer conditions set forth in this document.” The cost of fulfilling those conditions turned out to be quite high.

Commercial service was once robust at Lake Tahoe Airport. Photo/Del Laine

The beginnings of air travel at Tahoe

But before there was a Lake Tahoe Airport, there was Sky Harbor. Located in Rabe Meadow in the mid-1940s and 1950s, down Kahle Drive from what is now Lakeside Inn. It was a dirt runway carved out of the meadow, where early fly-by-the-seat-of-their-pants pilots needed all the skill and courage they could muster to avoid landing in the lake or against a mountainside. There were no fueling facilities. Pilots came in over the mountains, then circled back over the lake toward the Sky Harbor Casino to land, which they could only do when there was no wind, and during daylight hours.

Former City Councilman and El Dorado County Supervisor John Cefalu, remembers, “My father-in-law flew in to Sky Harbor in his Stearman from Placerville. People in the basin, led by Harvey Gross and Oliver Kahle, realized there had to be a place where aircraft could land.”

It was only used from 1946 to 1956. A number of other areas around the South Shore were briefly used or proposed as landing strips, including float planes landing on the lake, areas in Meyers, Johnson Meadow in Bijou, Pope Beach and the undeveloped area which is now the Tahoe Keys.

On March 12, 1956, the Board of Supervisors applied for a $75,000 grant under the Federal Airport Act to construct Lake Tahoe Airport. The county put in $63,000 from “available reserves” and the board levied a 10-cent countywide tax over the next year, with the remainder to be paid over the subsequent two years to cover additional airport construction costs.

Lake Tahoe Airport officially opened Aug. 1, 1959. Seventy-five planes flew in that first day. It was open, but it was bare bones. An Aug. 6, 1959, Tahoe Sierra Tribune (precursor to the Tahoe Daily Tribune) article described opening day: “One by one, planes of almost every make and description dropped in. (County Airports Manager Malcolm) Wordell, seated on the steps of a trailer which had been converted into a ‘control tower’ was busy at the Unicom, a small portable two-way radio. Searching the sky with his powerful binoculars, Wordell would advise the pilots when all was clear for a takeoff or landing.”

There was no control tower, terminal, on-site weather reporting equipment, paved parking for planes or cars, runway lights, hangars, restaurant or other visitor amenities.

It was a festive opening nonetheless. The airport was operational just in time for the 1960 Squaw Valley Winter Olympics. In an Aug. 6 Lake Tahoe News article, correspondent Vivian Little wrote, “At last you can fly to the lake in the sky! A phrase coined by Malcolm Wordell, Airport Manager.”

The official dedication was conducted the weekend of Sept. 11-13, 1959, with festivities overseen by master of ceremonies singer/actor Dennis Day. California Lt. Gov. Glen Anderson was a guest speaker, and the first Miss Tahoe Airport contest was held, with nine “beauties” competing in demure one-piece swimsuits. But it rained and rained — perhaps a hint that the airport’s high-flying honeymoon might be short lived.

The August 1959 edition of the Pre Flight Air News, a monthly pilots’ magazine based in Oakland, reflected the excitement of area airmen. “Now, at last, the California pilot can jump in his plane with visions of jackpots dancing before him. He can zoom past the bumper to bumper crowds, and be well on his way to wealth … before the poor earthlings have cleared Placerville.”

El Dorado County was the first operator of the airport. Photo/South Lake Tahoe

A bumpy ride

Some of the “earthlings” in Placerville, it turned out, were not as thrilled about the airport. Its costs to county taxpayers raised West Slope dissatisfaction even before it opened. The El Dorado County Property Owners Association told the Tahoe Sierra Tribune in July that the airport was, “for the benefit of a few fly-by-night developers and cheep (sic) gamblers.”

South Shore chamber member Jerry Calvert responded in an Aug. 20, 1959, Tahoe Sierra Tribune article. He called the Taxpayers Association, “A group of obstructionists (who) are now trying to forestall the future of the airport.” Of the gaming industry, he said, “This element and those who conduct this activity are an important segment of our economy. There is absolutely nothing cheep (sic) about any of them.”

In the airport Master Plan it was preparing, Charles Luckman Associates suggested the county, “Consider the feasibility of obtaining financial support or advances from Gaming and Stateline Entertainment interests which would profit from immediate development of the Master Plan.”

Tahoe was growing — there was the impressive $150 million Tahoe Keys development, a $3 million Harrah’s expansion, an explosion in building permit applications, a shopping center in Tahoe Valley, new schools, and the airport, which was seen as a vital component in all that growth. Not everyone was thrilled with this either.

“Only the people in Lake Tahoe wanted it,” Bill Johnson told Lake Tahoe News. “It was the clubs who were the pushers at that stage. I didn’t care for the airport being there. I didn’t care for the Tahoe Keys being there.”

The FAA has provided a substantial amount of money to help keep the runways and tarmac in shape. Photo/LTN file

The good and the bad

Shortly after its festive opening, there were three crashes at the airport all within a week, with two fatalities. Safety became an issue. Failure to gain altitude on takeoff was the problem in two, with one plane crashing and catching on fire and the other ending up wedged into a pine tree. Wordell defended the airport as safe, charging the accidents to “pilot error,” specifically the failure to recognize the effects of density altitude — the lower performance levels of planes at high altitude in hot weather.

In late 1959, a density altitude warning system and weather-reporting instrumentation were put in place along with leases for car rentals, limousine service, and a gift and tobacco shop. A rudimentary runway lighting system was approved by the FAA in October 1960 and the airport began 24-hour operations. There was still no control tower.

Hopes for the airport remained high on its third birthday in September 1961. A Lake Tahoe News article [the former print version of LTN has nothing to do with today’s online news site] of Sept. 9 affirms enthusiastically, “The fast growing baby thus far is fulfilling the growth potential, if not exceeding that which was predicted for it even prior to birth.”

Adjoining lands were purchased to provide the “clear zone” required by the FAA for operations by four-engine aircraft. Land from the Barton-Ledbetter family was purchased through a complex arrangement with Harrah’s South Shore Corporation, which agreed to pay $60,000 in landing fees over the next five years to cover the county’s $300,000 matching share to acquire the land and extend the runway. An FAA grant paid the other $602,000. Additional land was later purchased from Harvey Gross and others. The runway was extended to 8,541 feet in 1962.

On March 1, 1964, a Paradise Airlines Constellation bound to Tahoe from Oakland, carrying 85 passengers and crew, crashed in a blinding snowstorm on a peak just above Genoa, killing all aboard. Relatives of victims claimed in their lawsuits that faulty weather reporting by the county was to blame, with some saying that had there been a control tower, the tragedy could have been averted. Later that month, the Board of Supervisors approved funding for land acquisition for a control tower, putting off runway work at the Placerville airport for a year. The tower was completed in December 1964, and formally dedicated in June 1965. Tahoe pioneer Glen Amundson, who had also flown into Sky Harbor in the ’40s, cut the ceremonial ribbon by flying through it in a plane.

On its fifth birthday in September 1964, a Lake Tahoe News editorial still touted the airport’s money-making potential. “There can be little doubt that the Lake Tahoe Airport has a strong effect on the economy of the area and will have even more in the future.” But the airport was losing an average of $20,000 a year, and additional airport improvements were slow in coming. Del Laine remembers, “There was always some conversation about the cost of running the airport. The bottom line no matter where you are is money. Attitudinally, it is where the county was.”

Today Lake Tahoe Airport is busiest during the celebrity golf tournament each July. Photo/LTN file

Local control always elusive

Tahoe Valley’s desire for local control was growing, but it wasn’t new. A Sept., 17, 1959, editorial in the Lake Tahoe News entitled “Men or Mice” urged Tahoe Valley residents to stand up to the county. “Lake Valley may be the step-child of El Dorado County, but there is a point to how much we must be forced to take …. Let’s act like men and not mice.”

On Nov. 30, 1965, Tahoe Valley citizens did just that when the city of South Lake Tahoe was incorporated. Unfortunately, the hopes for local control were soon dashed by the emergence of organizations that believed they also had a say in the future of Lake Tahoe. The League to Save Lake Tahoe was formed in 1965, and supported the formation of a regional agency to oversee the lake. CTRPA (California Tahoe Regional Planning Agency) was formed in 1967, and its successor, the bi-state Tahoe Regional Planning Agency (TRPA), in 1969.

Additional outside regulation came from the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB), which had authority over airlines’ entry into or exit from domestic interstate airline routes as well as fares. The California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) had control over intrastate flights. Tahoe felt it was “underserved” by commercial carriers, but getting CAB approval for new routes was difficult. It hinged on whether the carrier was classified as interstate or intrastate. This led to some creative nitpicking. In 1966, Pacific Airlines contended that Paradise Airlines’ flights to Tahoe from inside California were actually interstate, because their passengers went directly from the airport, often in free shuttles provided by Harvey’s, to the clubs across the state line in Nevada to gamble, in effect using the California airport to serve Nevada interests — a theme which has persisted throughout the airport’s history.

The county was growing tired of carrying the financial burden for an airport many felt was of greatest benefit to the gaming properties across the state line and the newly-incorporated city was tired of fighting for needed improvements. Pacific Airlines, in fact, was so upset about the airport’s deteriorating facilities that they threatened to stop flying into Tahoe if they were not upgraded.

On Jan. 4, 1966, the City Council, “… decided unanimously that the city should try to acquire the airport and then make decisions as to operation.” County Supervisor Joe Ronzone agreed and offered his support. “The airport,” he told the Mountain Democrat, “is a benefit to the entire county, but its prime benefit is to the Lake Tahoe area, of course. As it is, under county jurisdiction, serious problems are created and many of these would be removed if the people at the lake had full control.”

He told a chamber luncheon in Tahoe that February, “You can get the airport at no cost. … If the city will come to us with a proposal, we’ll accept it.” City Councilman Gene Marshall immediately tried to get the council to prepare a proposal to acquire the airport, but they opted for a feasibility study instead. Marshall, exasperated, told the Tahoe Sierra Tribune, “…too many studies and not enough action.” This also became a recurring theme.

In1966, the city began exploring the idea of creating an airport district with taxing authority, with boundaries similar to those of the Lake Tahoe Unified School District. The first-year tax rate would be less than 0.04 cents per $100 of assessed valuation, and in five years, then City Manager John Williams believed, the airport would be on a “paying basis.” The county had already spent $1,801,937.33 to-date on facility improvements and $300,000 on operational costs and another $1,987,900 was still needed. With great foresight, Williams urged quick action to increase commercial flights into Tahoe, as the Reno Airport was “a major continental air facility” which was already drawing off fly-in visitors.

Williams presented the idea to the supervisors in 1967. They directed county counsel to “prepare the necessary papers to begin formation of an Airport District,” and later requested a feasibility study, but no formal action was ever taken.

Supervisor Johnson, and the Lake Valley Taxpayers Association he helped start, were opposed to the airport district. “I thought they should dig a tunnel and use the airport in Minden,” Johnson said. Lake Tahoe Airport, the group told the city in a letter, “will never be able to accommodate the planes of the future. … Minden airport will eventually be developed to handle even the largest planes.”

From 1967 until its eventual annexation in 1983, there was much talking, but little doing. In 1968, Williams broached the idea of a city/county Joint Powers Authority (JPA). Meanwhile, the cavalcade of airlines serving Tahoe continued. Hughes Air West and Holiday Airlines ended service to Tahoe in 1974 and 1975 respectively. In 1975, Air California (AirCal) and Pacific Southwest Airlines (PSA) began service using Lockheed Electra turboprop aircraft.

In May 1977, a management agreement for operation of the airport by the city was discussed and another feasibility study prepared, but it never penciled out. County Airports Director Peter Boyes told the supervisors on June 6, “The central point concerning city acquisition of the Lake Tahoe Airport is money.” The city considered the offer, but at its July 5, 1977, meeting decided it, “was not interested in taking over the operation of the airport at this time ….”

A Lockheed Constellation in 1963. Photo/Dave Borges

Airport discord continues

Enplanement numbers at the Lake Tahoe airport began to rise. A new terminal had replaced the converted barracks. Airfield improvements were slowly being made with the help of FAA grants. Airlines were just transitioning from aging Lockheed Electras to jets. Noise first became a major concern. South Lake Tahoe residents protested the growing intrusion of aircraft noise into Tahoe’s peaceful environment by loud business jets and the 727-100 jets flown by PSA charters.

A series of petitions with close to 500 signatures were presented to the board. Then Al Tahoe resident Mary Lou Mosbacher summed up the concerns in her letter. “We are anxious,” it said, “that no jets are allowed to use our area as the noise is intolerable. … How much disturbance can be tolerated. … How important is the economic health of a community versus the physical and mental health of its citizens?”

In June 1977, the county passed an emergency ordinance making it unlawful for “pure jet aircraft to arrive or depart between the hours of 8pm and 8am, of any day at the Lake Tahoe Airport.”

When the board later considered amending the ordinance to prohibit commercial jets from landing or taking off at Tahoe, except those that met acceptable decibel noise levels, the business community, gaming and airline interests protested. Tom Davis, then a member of the chamber’s Aviation Committee, spoke in opposition to the ordinance. Representatives of AirCal and PSA said they would, “not be able to live with the restrictive measurement standards based on decibels.” CTRPA felt airport activity in general was “inappropriate for Tahoe” as it conflicted with their goals and policies to “restore Tahoe’s tranquility.” The board left the revised ordinance in “introductory status” awaiting purchase and installation of noise monitoring equipment for Tahoe. The economy versus environment debate was heating up.

In July 1978, the board again asked the city to consider a management agreement. The airport and equipment would remain the property of the county, with the city responsible for total airport management. The county would retain approval over the budget and all major capital improvements. City Finance Director David Millican pointed out the risks if the city were responsible for making up operating losses and providing matching funds for FAA grants. Again, it was the money. The city decided to wait and see.

In October 1978, the playing field changed forever when the federal Airline Deregulation Act was signed into law, removing government authority over fares, routes and market entry of new commercial airlines. The powers of the CAB were gradually phased out. Enplanements at Tahoe reached their peak of 294,188 in 1978, but after deregulation, quickly plummeted. Airlines could now choose to abandon less profitable routes, which generally meant less point-to-point service with greater focus on larger hubs.

In 1979, CTRPA contested AirCal and PSA’s requests to use jets in Tahoe, and both airlines soon terminated service. Using Electras in Tahoe was expensive, and they found passengers preferred taking jets to Reno instead. Del Laine, who was on the City Council then, remembers, “The airport wasn’t a big focal point for the local community. Many of us who used the airport would take the airport shuttle from Harrah’s (to Reno). Flights went where we wanted to go. I never used Tahoe as a base from which to travel a distance.”

Others apparently felt the same way. Enplanements dropped immediately to 169,683 and in 1980 to 68,729.

Environmental issues — like the Upper Truckee River — will always be a factor when it comes to making decisions about the airport. Photo/LTN file

Airport flounders

The county had begun a new master plan in 1979, but it was slow going and expensive. Concerns were raised by regulatory agencies over the adequacies of its assumptions and accuracy of its environmental documentation. Aspen Airways and Pacific Coast Airlines were serving Tahoe, but the airport budget was in trouble. A December 1982 letter from Kent Taylor, county CAO, to the board indicated, “During the month of November, the Airport Enterprise Fund had insufficient funds to meet payroll and other expenses.” That year, enplanements in Tahoe reached their lowest point of 37,533.

There was talk of the Tahoe Transportation District assuming airport operations as TRPA was getting ready to adopt its Regional Plan. A memo from Richard Milbrodt, TRPA acting executive director, to TTD’s CAO Kent Taylor in September 1982, notes, “The district board needs to know if the Board of Supervisors is agreeable to discussions regarding transfer of airport operations and the possible conditions that would be attached to such transfer.” It was talked about but never implemented.

In early 1983, the county began looking at other options for running the airport. A JPA was again considered with the city, Douglas County, and possibly Alpine County. “The county,” John Cefalu explains, “was disinterested in the airport and unwilling to put in their 10 percent (match for FAA grants). It was basically neglected. General aviation was having difficulty with the condition of the runways.” The massive landslide at Whitehall that closed Highway 50 that year highlighted the need for another reliable way in and out of the basin.

In April 1983, the city approved annexation of the airport from El Dorado County. Councilman Cefalu asked that a letter be directed to Douglas County, offering to work with their legal counsel “to develop a mechanism for shared responsibility of the Lake Tahoe Airport.” Such cost sharing never happened.

“When we initially took over the airport,” Cefalu recalls, “we thought we had Douglas County in our corner to put money into the airport and be a partner. Douglas County commissioners said no we don’t want to put our money into Lake Tahoe, but prefer to put it into our own airport in Minden.”

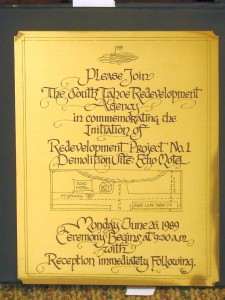

On Oct. 7, 1983, a ceremonial ribbon cutting by a phalanx of city and county leaders marked the official annexation of the airport. The city got control of the airport, but also took on responsibility for the monetary and regulatory problems that came with it, including completing the still-unfinished county Master Plan.

AirCal had just resumed service to Tahoe. Because of the landslide’s impacts, the Attorney General’s Office granted a 90-day exemption allowing existing flight levels while the city completed the Master Plan’s environmental documents. The city almost immediately increased AirCal’s flights, filing a negative declaration saying the increase had no environmental impacts. This started a virtual lawsuit landslide where all parties with any interest in or jurisdiction over the airport sued everybody else. In 1991, AirCal, caught up in the aftermath, terminated service.

Years of trying to reach consensus failed. In October 1992, to end the lawsuits, the parties signed the Lake Tahoe Airport Master Plan Settlement Agreement. “AirCal wanted to expand and go to (quieter) Stage 3 aircraft,” Tom Davis recalls, “but the lawsuits tied things up for a long time. The 1992 Settlement Agreement was the death knell. It put so many restrictions on that it couldn’t work out for an airline … good service out of Reno hurt us as well.”

A number of airlines including United Express, Alpha Air/Trans-World Express, Sierra Expressway, Allegiant Air, Tahoe Air and Reno Air struggled, but failed, to make serving Tahoe profitable. Tahoe Airline Guarantee Corporation (TAG), a privately funded entity, even put up a $1million subsidy in1994-95 for Reno Air, but once the subsidy ended, so did the service.

The last commercial carrier, Allegiant Air, pulled out of Tahoe in 2000 and the control tower, no longer funded by the FAA because of low service levels, closed in 2004 when the city alone could no longer fund it.

In 2003, the city had considered forming a JPA with El Dorado and Douglas Counties, and again in 2007, this second time at the request of then-City Councilman Bill Crawford. “What I was after,” he told the council, “was to bring three parties to share in the cost of operating this airport because all three parties are an interested party economically in this airport.”

South Lake Tahoe City Manager David Jinkens was tasked by council to, as he explains, “make contact with El Dorado County and Douglas County to determine if they would be interested in partnering with us to operate and share costs for airport operations. Neither officials of these counties were interested in doing so.”

Mike Bradford, Lakeside Inn CEO and longtime airport commissioner remembers the JPA idea coming before the Airport Commission. “I was the Douglas County rep,” he told Lake Tahoe News, “so I brought any proposals back over here and vetted them politically. I believed it would be appropriate to enter into some sort of cooperative agreement with the city and El Dorado County, but then when the city withdrew its (marketing) funding from the LTVA (Lake Tahoe Visitors Authority), we thought if they wouldn’t even help market, why would we partner with them on the airport.”

The Master Plan Settlement Agreement expired in October 2012, and the city began preparing a new Master Plan. Three public workshops were conducted, the last on March 16. At the City Council meeting the following day, the City Council voted to relinquish the airport’s FAR Part 139 certificate, required for commercial service, and focus instead on general aviation.

“It was during the Master Plan Aviation Demand Forecast,” Airport Director Sherry Miller explains, “that we learned how unlikely it was for air service to return.”

“The airline industry has changed,” Michael Hotaling of C&S Companies, the Master Plan consultants, told the council on March 17. With less competition and operating costs increasing, airlines need higher load factors and are very selective about airports they serve. Costs to meet Part 139 requirements for firefighting staff training and airfield reconfiguration are also prohibitive. A $1 million to $2 million subsidy/load factor guarantee, like Mammoth Mountain Airport uses, would be needed to entice an airline to serve Tahoe.

“STAR (South Tahoe Alliance of Resorts – an expanded version of the Gaming Alliance) was asked directly if they would participate,” Miller added. “They indicated they would contribute $250,000 per year to go toward advertising.”

Bradford confirms, “We went forward and gained through Douglas County an increase in transient occupancy tax to support air service. The understanding was that this would be to subsidize marketing for new service, but not to subsidize flights because of the negative experience we had with TAG. Then we inquired about the demand for service and it was never adequate to start the service.”

Councilman Davis asked how long it would take and how difficult it would be to regain the Part 139 certificate should a regional carrier want to serve the airport in the future. “I’d hate to give up something and then have the FAA say it’s impossible to get it back.” Hotaling responded that it would be “fairly simple.”

The city had long insisted, for years after commercial service had ended, that it was committed to seeing it return. Surrendering the Part 139 certificate marked a distinct change in focus. Not everyone agrees it was a good idea.

“I was disappointed,” former Lake Tahoe Airport Director Rick Jenkins, told Lake Tahoe News. “I understand they were concerned about the costs of keeping it but once you give that certificate up and try to get it back, it’s almost impossible. They won’t be able to walk the dog backward.” He added, “A small commercial airport doesn’t make a lot of money from service, but communities make tremendous income. I don’t think it’s true (commercial service) can’t come back without a subsidy. There would be people who want to fly in here.”

Former South Lake Tahoe Chamber of Commerce CEO Duane Wallace agrees, “I think based on how quickly the airline industry goes up and down, I wouldn’t have done it. There are grants available to small airports all the time. To give up on something that’s a possible major asset in the future makes no sense to me.”

“I think they’re giving up too soon,” John Cefalu believes. “Today, the way airlines operate (commercial service) is unlikely but over time circumstances change. There are people out there who want the airport to revert to its natural state. I’ve heard the [California Tahoe] Conservancy wants to put up the money and pay back the FAA (for federal grants). That would be a mistake.”

Others see it differently. “The League applauds the city’s move,” Darcie Goodman Collins, executive director of the League to Save Lake Tahoe, explained, “as it shows City Council agrees that commercial air service is not appropriate for Tahoe.” The League would like to see the wetlands in the airport’s stream environment zone restored. “We believe the area would provide more value if more of the land were once again acting as a natural filter for the lake, with its paved footprint reduced and airport operations greatly scaled down.”

Some feel the airport serves many important roles. “Its value is multi-faceted,” Del Laine said. “It’s obvious it brings people here to enjoy our area, but it is also an important tool in a fire emergency. It’s invaluable.” David Jinkens added, “The Lake Tahoe Airport is an important transportation facility, an economic asset and an emergency management asset for the city of South Lake Tahoe and the Lake Tahoe region.”

The city has indicated it’s looking into ways to enhance the airport’s revenue potential as a general aviation airport. It plans on conducting a citywide economic study, of which the airport will be a part. Bill Crawford thinks tapping the airport’s potential is vital. “We have the airshow in the summer, but you have to do more. Several times a year, have a real fly-in for general aviation. You have to promote it.”

Fifty-six years ago, the airport opened to unlimited expectations, but early on clear battle lines were drawn over its economic value and who should control it. It has not been just a struggle over airport funding and commercial service, but rather a reflection of the larger Lake Tahoe struggle to perfect the delicate balancing act between economy and environment.

If it is true that, “He who has the gold makes the rules,” it will be interesting to see who has the gold and who makes the rules for Lake Tahoe Airport’s future.