Heavenly at 60 — a ski resort for the ages

Heavenly started out small 60 years ago, but has grown to be one of the largest ski resorts in the United States. Photo/Heavenly Mountain Resort

By Susan Wood

It’s taken more than divine intervention to keep Heavenly Mountain Resort operating and successful for the last 60 years.

It’s taken a group of dedicated, resilient, ambitious individuals – some as ski bums in other lives – who have overcome tragedy and embraced triumph. They reflect fondly on this dual-state South Shore ski area. All have things in common: They love to ski and are willing to go the extra mile or extra effort to make it a memorable and family-filled experience.

“I’m always nostalgic about Heavenly. I always think about when my dad ran the resort,” said Bill Killebrew, who at age 23 took over as chief for his father, Hugh, when the elder Killebrew was killed in a plane crash on Echo Summit with three others in August 1977.

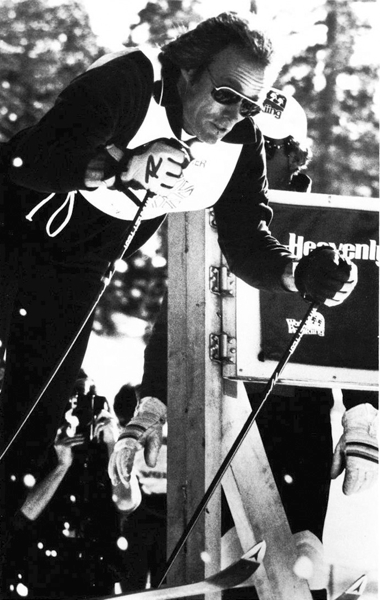

Clint Eastwood competes in the John Denver Celebrity Ski Classic. Photo/Heavenly Mountain Resort

It was the heyday for Heavenly, ushered in by Hugh Killebrew’s zest for fun, showmanship and racing – most often on World Cup.

When he perished, the young Killebrew had to fill a tall order: get the ski area out of debt, deal with losing his father and take care of the employees.

“None of us knows how we’re going to react in these times. For me, when I saw my dad’s airplane on the road, it was real. I knew he was dead. I put aside my emotions and drove to the nearest telephone. I spoke to my dad’s secretary (current day executive assistant Nancy McCoy) and arranged to talk to the managers,” Killebrew told Lake Tahoe News from his Stateline office. He had a steely resolve that thrust him into autopilot.

“And I wanted to be the one to tell my mother,” he said of Eleanor, who as a consummate hostess ran many of the major events at Heavenly throughout the 1960s and ’70s.

Killebrew, who essentially grew up with Heavenly, worked as a ditch digger, heavy equipment operator and in lift construction. He raced in the winter. In summer, he hiked with his father as a teenager and learned about the constellations. To this day, Milky Way Bowl, Big Dipper, Little Dipper and Orion on the Nevada side that opened in 1968, serve as a fitting tribute to those cherished father-son outings.

Malcolm Tibbetts’ contributions to the resort are memorialized at the midstation of the gondola. Photo/Susan Wood

The UC Berkeley graduate felt driven to carry on his father’s plans for snowmaking, operations that have saved many a season at this mid-town ski area. Countless explosions and engineering ingenuity later, pipe was laid on Maggie’s, Patsy’s and World Cup runs.

But since Mother Nature has the last say, the snow melted in snowmaking’s infancy. And there went the money.

In 1978 around Thanksgiving, Killebrew made the last payroll, exceeded his credit card limit, laid off most of the staff and made an appointment to file bankruptcy papers. But one Sunday brought about a milestone when the rain turned to snow. He got a brilliant idea to mark the end of drought with two days of free skiing. The daring gamble paid off. He burned the bankruptcy papers and called the media. Reservation lines were slammed, and 6,000 skiers showed up the first day and another 7,000 on Thanksgiving Day. The major networks showed up, and Heavenly made a mound of cash from meals and rental equipment.

Incredible views have always been a selling point for Heavenly. Photo/Kathryn Reed

Lessons learned and passed on

Heavenly’s origin had humble beginnings. In 1947, Lee and Daisy Miller built a warming hut in Bijou Park where skis and boots could be rented near a rope tow that transported skiers up 1,000 feet. At times, they even erected floodlights for night racing.

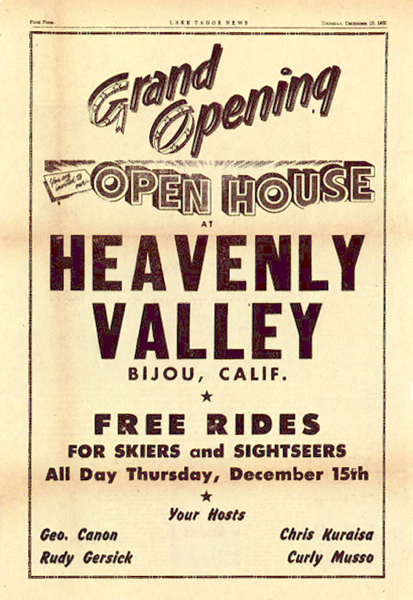

In 1951, Miller leased the Skiway to Bill Sutherland. Four years later, Miller turned over the operation to George Canon, Rudy Gersick and Curly Musso – who with Chris Kuraisa, a local casino owner who arrived in December 1953, had visions of promoting South Lake Tahoe as a winter destination for tourists. As hotel operators, Rudy and Trudy Gersick pitched the idea of visitors staying at the Ski Run Lodge and skiing with local instructor extraordinaire Stein Eriksen. In only a year, the Olympic gold medalist and world-renowned skier ran the ski school. (Eriksen died last week at age 88.)

No one was particularly wealthy at the time, but the early players were rich with dreams of placing South Lake Tahoe on the ski map for good. They were visionaries – a theme that carried on with subsequent owners, operators and planners.

Take Kuraisa, the founder. Not only did he lose his son in a fatal bicycle accident two days before opening, he endured immense financial challenges and hardships, but came out ahead in the end.

First, Kuraisa placed his life savings in the Tahoe Sport Center store when he arrived and got into the ski industry with a rope tow. Sutherland sold the rope tow to Kuraisa for $1,950 in cash, with a $50 option attached to the property Sutherland was originally selling for $3,750. Dorothy Kuraisa was nervous about living on the edge with her husband spending the last of their grocery money. But according to Heavenly’s chronicled history, Chris Kuraisa pledged the investment in what become to be known as Heavenly Valley would produce a return because of snow in the forecast the night of the deal day. The next day, the two feet brought out skiers spending $483 on lift tickets and sandwiches.

Heavenly Valley opened in December 1955 with a double chairlift on Gunbarrel, several rope tows and the Pioneer Warming Hut.

Building from the early investment in the mid- to late 1950s, the aerial tram was constructed in 1962. This opened up the mountain to year-round sightseeing from the ridgetop that provides Heavenly’s sweeping, signature view and took skiers to the backside of the mountain.

The site has transformed into various hang out eateries and watering holes. (In 2003, the Monument Peak restaurant at the top of the tram was the setting for a party honoring founding partners Patsy Gilman Wood and husband Bob, who were instrumental in getting the tram off the ground.)

There’s even a funny account of Patsy delivering dozens of doughnuts for one of the races and losing several of them as they rolled down the Face.

The 1960s and ’70s at Heavenly Valley established a reputation for celebrities and contests honoring beauty and speed.

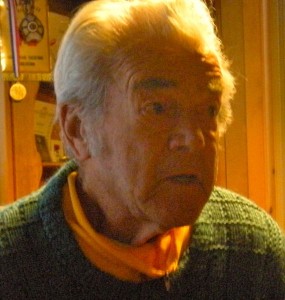

Martin Hollay

Martin Hollay, who is in his 90s and still lives within walking distance to the tram, skis most every morning. He remembers with affection the early days of his 30-year career with Heavenly. A glove maker from Budapest, Hollay has worked as a groomer and patrolman. For years, he’s made custom ski gloves for the Heavenly patrol. He was honored for his work in 2002 by skiing the Olympic torch down the World Cup run before it made its way to Salt Lake City.

“Skiing may be more crowded, but it really hasn’t changed to me. It’s just as it was before,” Hollay told Lake Tahoe News recently.

He sticks to Heavenly, and in particular the tram, as his method for getting on the mountain for good reason.

“It takes me almost an hour to drive anywhere else. In that time, I’ve already made turns already,” he said.

The Killebrew years

It took a former submarine commander in World War II, airplane pilot since a teenager and San Francisco lawyer to steer the ski area into the generation of Heavenly dreams.

Hugh Killebrew took over Heavenly Valley at a time when “skies the limit” fell over the world of skiing. Being a visionary, he knew that being at the mercy of Mother Nature meant making other arrangements to keep visitors and locals interested in paying for the sport that was growing in popularity.

Pop culture in the 1970s spawned the John Denver Celebrity Ski Classic and Chevrolet Freestyle Championships, among other races. The Heavenly Blue Angels, the first alpine ski club, provided growing interest in many skiers improving their skills.

The 1970s also brought about what has become known as the Hot Doggers of Heavenly.

The gondola under construction. Photo/Heavenly Mountain Resort

Malcolm Tibbetts, former vice president of mountain operations, was one of them.

At age 23, Tibbetts started with Heavenly as a ski patroller in 1971. He’s held posts as the assistant director, ski patrol director and mountain manager. Tibbetts was so instrumental to Heavenly’s growth, an honorary plaque was installed at the midstation of the gondola to commemorate his contributions to snowmaking, designing the midstation and getting the gondola off the ground in 2000.

Tibbetts, 66, grew up and later served in the military in Germany on skis – having never missed a winter in 60 years. He hails from New Hampshire and plans to return to the East this spring to hike the Appalachian Trail, which sits on his bucket list. Along the way, he’ll be thinking about completing his memoirs – much of the life story about his tenure at Heavenly.

After serving in the Armed Forces, he packed a Volkswagen van and traveled the country.

“All over, I heard about Tahoe and had a friend here,” he told Lake Tahoe News.

Money was lacking at the time, but Camp Richardson provided a free spot to camp if he cleaned the bathrooms and collected fees. Hollay gave Tibbetts his first job at $1.77 per hour.

“I came here for a year of ski bumming,” he said. After a year of “hot dogging” at Heavenly over gigantic jumps, he broke his back doing a flip. Even that didn’t keep him from hitting the slopes.

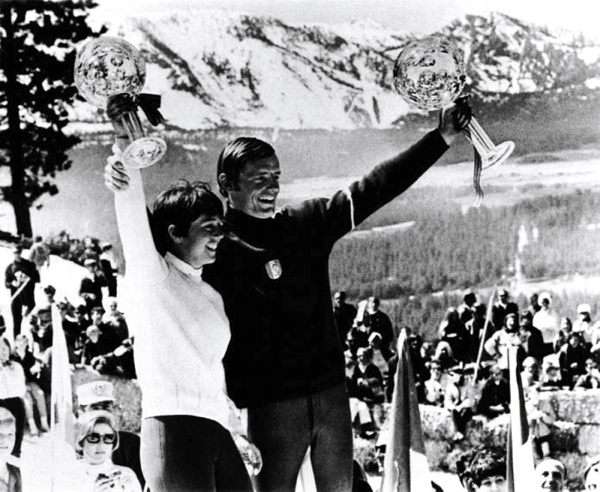

He skied with the likes of Eriksen, having to race against him in the World Cup. There were races, parties, events and challenges.

“I had a great career. Who can claim to have an office over 22 square miles,” he said. “I met my wife Tere here and raised two kids.”

Even after knee surgery, Tibbetts went out skiing recently and shared feelings of nostalgia.

“I look all around and see things I built,” he said at the base of the Comet chairlift.

Nancy Greene and Jean Claude Killy when World Cup races were held at Heavenly. Photo/Heavenly Mountain Resort

Tibbetts commended the younger Killebrew for getting Heavenly out of debt in the late 1970s and having the foresight to make snowmaking a priority after the elder Killebrew died.

“The plane crash was the saddest time. There are certainly events in life you remember where you were. That was one of them for me. The ski area was in ruins when Bill took over. He was incredibly lucky,” Tibbetts said of the good fortune bestowed on Bill at his time of need.

At the time, a lift ticket was $3.50.

“Now you can’t buy a cup of coffee for that,” he said.

Snowmaking didn’t come without its challenges. Tibbetts recalled renting pumps and closing off Keller Avenue’s fire hydrant to get snow to fly on the World Cup run.

“We were babes in the woods and learned the hard way,” he said.

One pipe blew out and temporarily blinded him. He was forced to count the numbers on a rotary-dial phone to call his wife.

With snowmaking and all things Heavenly, what a ride it was.

How has the ride changed?

Tibbetts thinks back on the Killebrew days as a period where he could waltz in the office and give his two cents on Heavenly operations. He didn’t always see eye-to-eye with the Killebrews, but he said they always respected his opinions.

Heavenly is now a year-round resort with ropes courses available in the summer and more activities coming soon. Photo/LTN file

In 1990, the Kamori Kanko company bought the ski resort from Killebrew – taking the first step in Heavenly’s transformation into an international company. The Japanese investor was known for taking good care of the employees, according to Tibbetts. A year later, the Mott Canyon chairlift on the Nevada side opened. The year after that, the top of the mountain Sky chairlift made its debut as an express lift.

By that time, Kamori under the direction of chief Dennis Harmon had bragging rights to 65 percent of snowmaking coverage and lifts dotting two states.

Owner Katsuo Kamori endured his own tragedy when he lost his son in a fatal accident.

In 1997, Kamori turned over the reins to Les Otten of American Skiing Company – a corporation with roots in the East.

The following year, Sonny Bono, the entertainer and congressman, was killed when he hit a tree while skiing.

Despite the ups and downs of Heavenly’s history, ASC pursued Kamori’s tireless efforts dealing with government agencies on a $4 million master plan for the resort amid environmental regulations, one of the resort’s largest challenges.

The gondola opened in 2000 due to ASC’s efforts – with employees taking part in the physical end of laying the cables. When it opened, Tibbetts recalled it as “the scariest day of my whole career because of my decision to run that thing” since the spotlight was on the ski area. The gondola was finally the link between the casinos at Stateline and the high part of the mountain.

“We had (wind) gusts of 70 miles per hour,” he said.

The gondola may have been a blessing to the town, but it came at a price for ASC. Its stock was so low – less than $1 — by the time it sold Heavenly to Vail Resort, it was delisted on the New York Stock Exchange.

Vail leads the way

The Broomfield, Colo.-based company has invested tens of millions of dollars in Heavenly, launching the South Shore ski area into the corporate arena in 2002.

Most stakeholders and observers see the change in atmosphere as “different.” Many of the ski resorts from the 1950s to 1980s were run by families. Now the ski industry has gone corporate, with stockholders to satisfy, as well as cash to improve tired infrastructure.

The Heavenly Village with the gondola links the town to the mountain. Photo/LTN file

And Heavenly was special to this Colorado company. Having a resort in California helped it diversify its regional portfolio in case other areas where it owns resorts have tough times. Take a look at its first Chief Operating Officer Blaise Carrig, who moved from running Heavenly to being in charge of western mountain operations at corporate before retiring last summer.

Heavenly has spawned many a ski industry career.

Former Vice President of Planning and Governmental Affairs Stan Hansen started as a ski instructor and patroller in 1966 before retiring in 2001.

“I used to say I degreed in Hugh Killebrew,” he said from his Puerto Rico home where he relishes the retirement life. “Heavenly’s come a long ways.”

Hansen embraced working with Tibbetts during Heavenly’s growth years.

“Malcolm could build anything,” Hansen said, adding the gondola was “a destiny”. The early pioneering Heavenly stakeholders thought about the benefit to hooking the town with the upper mountain. Kamori wanted it. Marriott stepped aside from the ground level, but built its two hotel condominium projects at Heavenly Village at the base in 2002. Vail swooped in when it saw the promise of having the eight-person cars whisking skiers and boarders up the mountainside.

Even former President Bill Clinton endorsed the idea. Upon his visit for the Lake Tahoe Environmental Summit in 1997 he mentioned the lift specifically.

“I’ll never forget all of us sitting around in a meeting, and Clinton said: ‘I think you should build a gondola from the town to the top’,” Hansen said, snickering. The governmental affairs guru looked over at Andrew Strain, who worked for the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency – the regulatory agency tasked with keeping projects in line the region’s lake clarity mission.

“He rolled his eyes and said: ‘You got to him’,” Hansen said of Strain, who now works for Heavenly as the vice president of planning.

“It’s been an interesting ride,” Hansen said.

Don Evans, Heavenly’s marketing manager, also placed the gondola construction in 2000 on the top of the list of pivotal moments for the ski resort.

“What hit me is I knew all the people building it, and they got in such good shape, they looked like body builders. I barely recognized them,” Evans said.

Evans said he has thoroughly enjoyed his tenure at Heavenly. He arrived in 1974 after leaving Pennsylvania, where he taught skiing.

“The first day I went out on Heavenly I didn’t know much about the place,” he said. “We all went out. It was a cloudy day with fresh snow. When I skied the California side, I thought ‘I’m skiing with the big boys.’ I realized I was in a pretty special place.”

Through the years of promoting it, he’s learned about and embraced Heavenly’s storied past.

“We’re lucky to live here. I’ve felt such a sense of community,” Evans told Lake Tahoe News. “I look at where I am now and where the mountain is now – there’s been a real organic connection between the mountain and the town.”

Even those who move away get the connection.

“I started skiing there in the seventh grade,” said Linda Jahn, daughter of South Lake Tahoe’s resident historian Betty Mitchell. The 69-year-old got nostalgic about being a member of the youth ski club – the Heavenly Blue Angels.

“Everybody knew everybody back then,” she said. “I skied every day after school. This was such a memorable time.”