Redevelopment keeps redefining S. Lake Tahoe

Having the gondola at Heavenly go from the village to the mountain transformed the skiing and tourist experience on the South Shore. Photo/Heavenly Mountain Resort

Publisher’s note: This is one in a series of stories Lake Tahoe News will be running leading up to the 50th anniversary of South Lake Tahoe on Nov. 30.

Resilience, humility, irony. This describes the state of redevelopment in South Lake Tahoe from the early days of Virginia Slims commercials to the mid-1980’s burst of tourism to today’s absence of California government in sanctioning the way to finance change.

As the city this year celebrates its 50 years in business, the look and feel of this mountain town next to the largest alpine lake in North America reflects a state of flux in the last half century.

A hint of early, unofficial redevelopment came about in the 1960s upon Squaw Valley bringing the Winter Olympics to Lake Tahoe. The South Shore city accommodated the perceived influx of visitors by building rows of motels along the major thoroughfare, Highway 50. Right or wrong, the infrastructure in many respects stayed planted for decades.

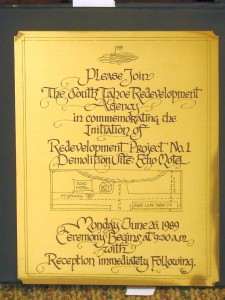

Before ceasing to exist three years ago as a result of the 2011 Budget Act, state redevelopment agencies had been around since 1943 as a mechanism for growth for cities. But most at that time relied on federal funding. It wasn’t until 1952 that cities got into the swing of using the state’s money to fund such ventures – eight years before the Games arrived in the Tahoe area. Talks were even under way in July 1966 of building a convention center on Happy Homestead property, a proposal that never materialized, albeit how easy it seemed to build back then.

In the early ’60s, building required an 8½ x 11 site plan and power permit. Now, reams of paper and a bankroll are necessary for construction on most projects.

Then in the mid-1980s, a group of moving and shaking city officials realized that to compete, ironically with places like Vail for tourism dollars, South Lake Tahoe would need to reinvent itself. When the city’s planning department saw “what was coming” as community matriarch and former city Councilwoman Del Laine pointed out, efforts were under way by officials to get on the improvement track.

“We realized we could improve on what we had,” Laine told Lake Tahoe News.

There were meetings and more meetings in 1987, some as far away as the League to Save Lake Tahoe’s home base in San Francisco. Along with the lake’s regulatory watchdog Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, the League’s environmental advocacy leaders were at least curious about what redevelopment could do for the city on both sides of the town from north to south.

Today, current projects are still in the works from the Y’s just approved Tahoe Valley Area Plan to the Stateline area’s constantly evolving condominium hotel-retail project where a convention center was once planned on 11 acres bordering Cedar, Stateline and Friday avenues, and Highway 50.

At this time, the notion of the environment and economy working in harmony was what kept the redevelopment wheel in motion.

“South Tahoe would have been in the same shape as other failed tourism communities,” former City Attorney Dennis Crabb said, while also listing Seaside near Monterey and Jackson in the Gold Country as other examples.

A pretty lake wouldn’t have been enough to maintain a pristine environment and an economy full of potential. With McDonald’s on Lake Tahoe Boulevard flooding every year because of a lack of storm drainage infrastructure and motel owners seeking more business to sustain them, citizens appeared eager for something to change.

“Motel owners were going to get bailed out, and that was salvation,” Crabb said, while also building a case for nearby retailers tacking onto the gravy train.

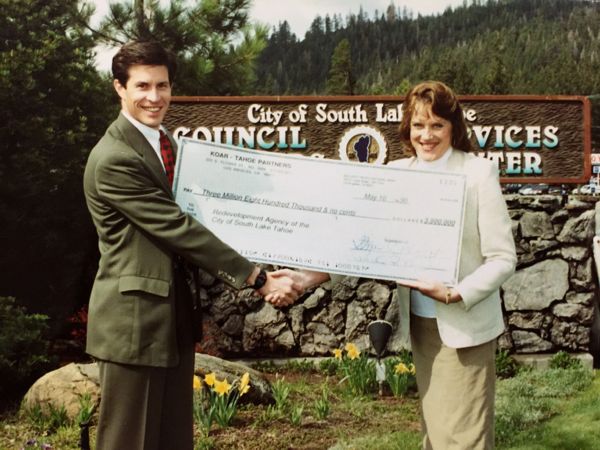

Steve Kenninger with KOAR, developers of Embassy Suites and what is now called Lake Tahoe Resort Hotel, and then South Lake Tahoe Mayor Neva Roberts in 1990. Photo/South Lake Tahoe

Nothing worth doing comes easy

After the city incorporated in 1965 and the lake was legally divvied up by jurisdiction in 1970, the town was in desperate need of reinvention.

Kerry Miller, the city manager who arrived in June 1987, remembers redevelopment’s humble beginnings like they were yesterday.

“The Tahoe basin came off a three-year building moratorium, with the League’s legal challenge of TRPA, and we realized that as a result, the economy suffered and tourism suffered,” Miller said from his home in Folsom.

In days long before its flagship ski resort owned anything here, Vail continued to develop during the lake’s moratorium. The Colorado town’s achievements cut into ski area tourism, and Tahoe faced a visitation drought down the road that would make the recession from a few years ago look like happy days.

“It became likely Tahoe as a tourist destination would not be able to compete,” Miller told Lake Tahoe News.

City staff prepped some plans. An agreement was struck with the state Attorney General’s Office. Measure C, which passed in November 1988, put transient occupancy tax in city coffers – 10 percent across the town, 12 percent in project areas. And what a project area South Lake had, resembling an oversized barbell from one side of town to another. The South Tahoe Redevelopment Agency zone spans 173 acres from Herbert Avenue to Stateline Avenue. Later on, the zone leapfrogged to Harrison Avenue at midtown near El Dorado Beach and at the Y.

In the late-1980s, all approvals were reached, movement was made to secure bond financing and the land assembly came together starting with Lake Tahoe Vacation Resort at Ski Run Boulevard.

“The citizens were involved during the entire planning process,” Miller said.

Sure, there were naysayers but “surprisingly not a lot,” the former city official added in a tone that seemed to almost surprise him.

“People had objections. There were people bemoaning the idea of change. But it was overwhelmingly positive. The town looked dated. Tahoe’s beauty ‘no matter what’ had a dated quality to attracting visitors,” he said.

Eminent domain – the government-sanctioned taking of property for improvements to alleviate blight, in its truest sense – represents the all-encompassing main objection to redevelopment. But bringing fair market value and a relocation plan to the table for the displaced seemed to ease the pain somewhat, and citizens were ready for a change, Miller recounted.

Improvements were being made, but then “a funny thing happened” as the city endorsed the KOAR company’s plans for what was Embassy Suites bordering Stateline. The Gulf War in 1990 literally dried up the financial markets. The post-war recession “fatally affected” redevelopment for three years, Miller went on to say.

After the economy started to recover and Embassy Vacation Resort opened at Ski Run in 1995, the movement paved the way for a concentrated effort to go into the Park Avenue Project on the other side of the street bordering Stateline.

The birth of Heavenly Village

The major redevelopment undertaking resulted in Heavenly Village with its two Marriott timeshare condominium properties, 120,000 square feet of retail run by Gary Casteel who at the time owned the Factory Stores at the Y, a city transit station and parking garage, and a $25 million gondola built by Heavenly Mountain Resort in 2002.

Project 1 didn’t come without hitches and glitches. It demonstrated a sign of ultimate, stubborn resilience from the private and public sectors – almost to a fault.

First, the city Redevelopment Agency siphoned off $7 million from the general fund to finish the 110,000-square-foot project – a watershed moment announced at a meeting in May 2003 when the council got a wakeup call on monitoring its accounting department. The tab was financed and refinanced, thus raising the debt service in 2006 to $112 million to be paid over three decades. The city even paid out $12 million in legal fees associated with the $250 million project flanked by the Grand Summit and Timber Lodge.

Redevelopment was a lot like gambling – one, which paid off ultimately when considering, delayed tax-revenue benefits. The property once assessed at $15 million when the plan was adopted in 1988 had increased more than 20 times on the El Dorado County tax rolls according to statistics from a decade ago. Its value mushroomed then at $346 million, up $100 million from when the complex was completed.

Moreover, Heavenly’s parent company at the time – American Skiing Co. experienced a dive in its value on the stock market to the point shares sold for less than $1. The plummet resulted in a delisting from the New York Stock Exchange. It was the beginning of the end. At one point, it was doubtful the gondola would even get built.

To the rescue, Vail Resorts ended up buying the town ski resort a few years later – and has since poured millions of dollars into capital improvement projects.

Yet another hurdle to overcome, parking turned out to be an albatross of an issue. The money-losing $6 million garage turned into $9 million for the city. Parking at the gondola turned into a debate and debacle for years. Visitors either clogged the side streets until the city implemented a two-hour limit in the surrounding area to urge motorists to park in the garage or parked at Harrah’s back lot or at what was the Crescent V shopping center next door. The latter resulted in aggressive parking monitors ticketing visitors or in some cases grabbing their arms.

Something needed to give. City officials got creative, offering deals for parking in the garage, validation agreements with retailers and a turning of the cheek from the major casino in what was happening in its back lot.

Concrete and rebar constituted “the hole” for years until Owens Financial consolidated the properties and began incrementally developing the site. Photo/LTN file

The other side of the coin

Parking could still be an issue as one looks at the current Project 3 across the highway. Talk about evolution. The changing of management hands alone resembles a cross between a card game and a chess tournament. Harveys casino, then Marriott, then Lake Tahoe Development Co. – the latter run by a small, local development duo – was once in line to build the city’s largest proposed project once estimated at $410 million.

Upon breaking ground in 2007, the triangular-shaped project area on the lake side now called the Chateau Project where McP’s Tap Room serves as an anchor was supposed to house a major hotel and 200,000-square-foot convention center. The city was due to own the monstrous facility according to the ever-changing Owner Participation Agreement between the city and Tahoe Regional Planning Agency.

One challenge after another ensued.

Displaced and bought-out business operators kept the city in and out of court through the years. Legal fees mounted, with some business owners having better results than others.

At least Jim Hickey, owner of the former Union 76 gas station, came out ahead of the game.

“I thought everything was fair in the long run. I wished it would’ve happened a little faster, but I know the project was big. It took several months to close the deal,” Hickey, now an Internet marketer, told Lake Tahoe News.

All in all, there was the harsh reality that convention centers went out of style, a warning Charlie McDermid from Holiday Inn Express warned the city about when he waved a hotel-trend magazine at a heated City Council meeting years ago. Financing for the evolving hotel-condominium idea dried up.

With no performance bond in place for the city, L.T. Development Co. led by Randy Lane and John Sherpa consequently filed for bankruptcy. Rebar and concrete marked what was affectionately referred to in town by locals as “the hole in the ground” — much to the embarrassing dismay of the city.

The Tahoe Valley Area Plan has passed the regulatory hurdles and now awaits investors to transform the area along with the city which intends to create a green belt.

It’s a new game in town

But current City Manager Nancy Kerry, an idea activator, was not going to let this blemish lie unattended on her watch.

Even as the state pulled its support for redevelopment a few years ago, staff and L.T. Development Co. negotiated with Tahoe Stateline Ventures, a subsidiary of Owens Financial, for it to buy the parcels in the project area and with tweaked plans go forth with a scaled down version of what was to happen across from Harveys.

The 32-unit condominium project, absent a traditional hotel now, is now proposed with a pool, 19,477-square-feet of retail space (a third of its original size), streetscape improvements and public fire pits.

A little modesty never hurt anyone.

Owens Financial chief Bill Owens describes his undaunted dedication in three words: “Location, location, location.”

What keeps him interested sounds almost in line with what the founding fathers and mothers of redevelopment had in mind.

“I believe South Lake Tahoe has been maligned in public perception because of the older properties not being redeveloped. A lot of (business operators) don’t want to bother. We need this. You can walk to gaming, walk to the lake, walk to a ski resort. There are very few places on Earth you could do that,” he told Lake Tahoe News, adding working with the city has been “a pleasure.”

One could say he’s a visionary like Kerry.

He doesn’t wince at challenges. And between planning staff’s early caution led by Jim Marino about parking and sometimes dangerous pedestrian movement across the highway, there could be more issues. A Heavenly employee was hit by a motorist crossing the street in that area about a decade ago, severely injuring her.

There are the other considerations.

Owens would prefer not to have to deal with the slopes of the roofs as dictated by TRPA guidelines issued in 2007 for the project now estimated to cost almost half as much.

“(The roof slope) makes it more expensive to build, but it’s not something I can’t live with,” he told Lake Tahoe News.

But that’s all in a day’s work to people on his side like Joe Stewart of SMC Contracting. The contractor is a tour de force for building in the redevelopment area, namely the Park Avenue project, so he knows the drill.

It’s a good thing. Between a changing proposal, shrinking competitive market, nagging recession and no redevelopment agencies in 400 communities up and down the state, this isn’t easy.

“Heavenly Village was built with redevelopment funds. This one has zero public funds. In some cases, it makes the project go slower. I think the redevelopment agency was a huge benefit across the street. We should be lucky it’s built,” Stewart told Lake Tahoe News. “I feel like Bill Owens certainly stepped up and did something no one else would do.”

In August, Stewart expects the groundbreaking of the second phase.

All this is music to the ears when it comes to the last of the “redevelopment” oriented projects for civic-minded Paul Bruso, who has owned and operated Ernie’s Coffee Shop for decades.

Bruso was one of the early pioneering citizens to spearhead a plan for a remodeling of the Y where his restaurant he’s retiring from sits.

The Tahoe Valley Area Plan has undergone its own jerks and grinds as it makes its way into the future. It’s come to the forefront with issues over building height, project area and former Councilman Ted Long’s apparent push to spearhead taking over the plan from the citizen’s group years ago, elevating the debate.

But when all was said and done minus Long’s sarcastic “thank-you-very-much, we’ll-take-it-from-here” attitude, Bruso said he’s pleased with how the plan is materializing.

One thing he would like to see is better lighting.

“People who visit want to get out of their cars and walk. We want them to feel safe,” he said.

Overall, it’s “a good plan,” according to the restaurateur.

“It’s like (the city has) been thorough in what people want. They took all the necessary steps,” he said. “The whole idea is this town is going through a beautification process. Unfortunately, the Y is the tail of the dog.”